You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Journalism About Families’ category.

There are, of course, lots of big problems with journalism’s treatment of missing women. But I was struck yesterday by two headlines, both of which described their subjects as “missing moms.” Neither of the stories attached to the headlines—an AP story on NYT.com and a local news station’s story linked from CNN.com—suggested that the woman’s status as a parent was relevant to her disappearances (dropping children off at day care, or failing to do so, did figure into the stories of Susan Powell of Utah and Cortney Hudson in Massachusetts, but not centrally as far as I could tell).

So why would news organizations characterize the two women that way? I wondered initially if the women were full-time parents and the descriptor was being used as the equivalent to a noun describing a profession, as in a headline reading “Police Treat Missing Utah Banker as Criminal Case.” But both women have jobs outside the home. The only explanation I can think of is that the headline writers (and reporters themselves, who both used “mother” as the subject of their lede sentence) thought that defining these women by their relationships with their children would make the story more affecting for their audience. That or that the news organizations were making the (impossible and totally inappropriate) judgment that the women’s parental roles were somehow more central to their identity than other elements of their lives.

Of course the prospect of children losing a parent is affecting, and might easily have a place in a story about a missing person who is raising children. But choosing to elevate that element of a person’s life by literally defining her by it encompasses a judgment that no journalist is qualified to make. And if the search for affect was indeed the reasoning behind the “missing mom” meme, then the writers have violated what should be a standard of ethical journalism: it should rarely, if ever, prioritize a person’s value to others over her unique value as a human. We have a serious cultural problem if a story about a missing woman requires her to be a mother in order to tug at our heart strings sufficiently.

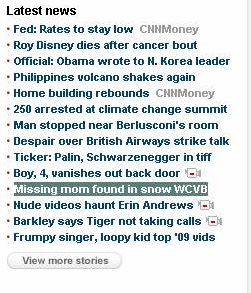

CNN.com front page “Latest News” 12/15/09, around 3:30.

It would be interesting to do a headline search in Lexis-Nexis for “Mom” and “Dad” and compare how often the described person’s status as a parent was of primary importance to the story. Without doing that, I can only say that it seems much less likely that a missing man would be described as a “missing dad” if his fatherhood were irrelevant to his disappearance. (Though he would almost certainly receive less coverage overall than his female counterpart.) He would be a “missing man” or possibly a “missing [representative of his profession].” Like “missing mom,” the latter choice reduces the missing person to one element of his life. While that reduction might also be problematic, most professions are less fraught with historical and sociological baggage than motherhood.

Once again it’s just me on the Usage Panel, but I’ve got another interesting issue to address, and lots of others have written about it, so I will consider my post as participation in an internet-wide “panel.” The question is what noun-phrases media organizations should use when identifying people who reside in or enter the U.S. in violation of U.S. immigration laws.

“Illegal aliens” and “illegals” are two answers that can be dispensed with pretty easily. When used in journalism, the legal term “aliens” suggests an exaggerated sense of strangeness, and the connotation with martians is unavoidable. Although it’s relatively rare to find uses of “illegal aliens” in major news organizations (cable news, as always, excepted), except in quotes, a quick Google news search found numerous examples from local news organizations. “Illegals” dehumanizes, defining a diverse group of people by one (negative) characteristic by employing the reductive practice of noun-ifying an adjective. In a 2006 press release addressing immigration terminology, the National Association of Hispanic Journalists states that “using [‘illegals’] in this way is grammatically incorrect and crosses the line by criminalizing the person, not the action they are purported to have committed.” “Illegals” is increasingly unusual even in headlines (where more accurate and ethical, but longer, phrases are sometimes eschewed for space considerations), though the AP seems to have few scruples about using the word, in headlines, the body of a story, or both. I don’t know how much control publications that use AP stories have over style issues like that, but it would be interesting to know to what extent they are allowed to impose their own style guildelines.

The interesting question for me is whether “illegal immigrant” is an ethical/accurate way to refer to people who enter or reside in the country illegally. It is by far the most common way of describing this group of people in journalism, the reason given usually being that it provides the most direct and truthful description. I’ve encountered a lot of compelling arguments against using this term, though. The first is that a substantial minority (about 40%, according to the most often quoted numbers) of those residing in the country illegally didn’t actually immigrate illegally, but overstayed their visas, and the term “illegal immigrant” obscures that group. Also, as I understand it, the charges against people who enter or live in the U.S. illegally are primarily (perhaps all? any lawyers out there who can help me?) civil, not criminal. And though “illegal” is still technically accurate, the word does suggest criminality to my mind. The main argument against “illegal immigrants” by the National Association of Hispanic Journalists is that “the term criminalizes the person rather than the actual act of illegally entering or residing in the United States without federal documents.” Ted Vaden, in a North Carolina News and Observer column, offers this distinction: “Illegal may be used to describe how people got here — “immigrants who are in the country illegally” — but not to describe the people themselves — “illegal immigrants.” ”

But if “illegal immigrants” is problematic, what term should replace it? “Undocumented immigrant” and “undocumented worker” are often raised as more humanizing alternatives. Although “immigrants” is an imperfect option for the noun, I think “worker” is even less accurate and I can’t think of a third option. “Undocumented workers” is a useful phrase only when the employment status of the people being described is relevant to the story. Otherwise, it doesn’t make sense as a replacement for “immigrants.” The primary argument against “undocumented”—made in both the Washington Post and the New York Times stylebooks—is that it is a euphemism. According to the Post stylebook (as quoted by then-Ombudsman Deborah Howell in an interesting column), “When used to describe immigrants, [‘undocumented’] is a euphemism that obscures an important fact — that they are in this country illegally.” In an October 2007 New York Times editorial observer column in which Lawrence Downes assesses several possible labels for people who enter or reside in the country illegally, he writes, “Someone who sneaked over the border and faked a Social Security number has little right to say: “Oops, I’m undocumented. I’m sure I have my papers here somewhere.” ”

Downes suggests “unauthorized immigrants,” which strikes me as an accurate description that avoids many of the pitfalls of both “illegal” and “undocumented.” (The San Antonio Express-News apparently uses “unauthorized,” and the term is also discussed in this thoughtful post about the labeling issue by writer Daniel Hernandez at his blog Intersections.) I like how “unauthorized” doesn’t simply define a group of people by their status under U.S. law, but gives some shape to the institution that would bar them from entry or residence. It also avoids the problem of referring to immigrants who possess faked documents as “undocumented.” I think I’ll make the switch to “unauthorized immigrant” in my own writing—when a short label is necessary—unless anyone can suggest a better option in the comments section.

But maybe more important than the choice of which shorthand to choose is the fact that any shorthand used to label a large and diverse group of people is bound to obscure some truths. Aly Colon makes that point eloquently in a Poynter Online “Diversity at Work” blog post:

As a journalist who has written about and edited many stories involving diverse issues and people from different backgrounds, my inclination is to avoid labels as much as possible. Try to describe as accurately as you can the people you are covering. The more specific, the better. What we, as journalists, think we save by using a label and fewer words, we more than make up for in confusion, bias, prejudice and distortion. Labels limit us. And they limit the reality we see.

One of the most frustrating elements of news coverage of the 2004 election for me was the persistence of the phrases “moral issues” and “moral values” in descriptions of socially conservative voting patterns. Obviously socially liberal positions come from at least as moral a place as do socially conservative ones. I doubt that reporters meant to imply that they don’t, but using “values” as a shorthand for social conservatism left readers with that strange and inaccurate impression. I was particularly disturbed at the tendency to describe support for anti-gay measures in that way, because while the issue of gay rights is emphatically a moral one, I don’t think that the right lies with the discriminatory side.

So I approached the coverage of the passing of this year’s four anti-gay ballot measures with trepidation. I found, however, that the 2008 coverage wasn’t as ready to equate morality with social conservatism, and in some cases mainstream news reports acknowledged that the winning side hurt people by denying them their civil rights. The main New York Times article opens with the moving image of “a giant rainbow-colored flag in the gay-friendly Castro neighborhood of San Francisco…flying at half-staff” over the success of California’s Proposition 8. And for the most part, support for the bans was attributed to “social conservatives” or “religious conservatives,” rather than the “values voters” of 2004. By framing Proposition 8’s passage as “paradoxical” in an election that was so historic for the history of civil rights in the U.S., a CNN story acknowledges that gay marriage is indeed a civil-rights issue. And it was heartening to see news organizations recycle the (accurate) language of Proposition 8 itself, which points out that the measure seeks to deny a right, “the right of same-sex couples to marry in California.” There were a host of good stories speculating about the emotional, legal, and practical effects of Proposition 8 on same-sex couples who had married in California.

New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof seems to think that this descriptive evolution is a problem—or that is in part how I read his election day blog post about the relationship between his papers’ reporters and social conservatism. Kristof’s post dismisses—correctly, I think—the claim that the Times has a political bias, but it frets about the paper’s socially liberal ethos. There may be truth to some of his complaints, and I haven’t thought much about the way the Times addresses issues like gun control and abortion. But Kristof also mentions the Times‘ coverage of gay marriage as a problem. He points approvingly to a 2004 column by then–New York Times Public Editor Daniel Okrent in which Okrent laments the absence of stories exploring “partner abuse in the gay community, about any social difficulties that might be encountered by children of gay couples or about divorce rates,” among other issues that he thinks are necessary elements of “the three-dimensional perspective balanced journalism requires.” Presumably he is suggesting that such stories are relevant to the question of whether gay marriage should be legal. In somewhat sarcastic language, Okrent bemoans the preponderance of positive stories about people who have been granted this right:

But for those who also believe the news pages cannot retain their credibility unless all aspects of an issue are subject to robust examination, it’s disappointing to see The Times present the social and cultural aspects of same-sex marriage in a tone that approaches cheerleading. So far this year, front-page headlines have told me that ”For Children of Gays, Marriage Brings Joy” (March 19); that the family of ”Two Fathers, With One Happy to Stay at Home” (Jan. 12) is a new archetype; and that ”Gay Couples Seek Unions in God’s Eyes” (Jan. 30). I’ve learned where gay couples go to celebrate their marriages; I’ve met gay couples picking out bridal dresses; I’ve been introduced to couples who have been together for decades and have now sanctified their vows in Canada, couples who have successfully integrated the world of competitive ballroom dancing, couples whose lives are the platonic model of suburban stability.

Every one of these articles was perfectly legitimate. Cumulatively, though, they would make a very effective ad campaign for the gay marriage cause. You wouldn’t even need the articles: run the headlines over the invariably sunny pictures of invariably happy people that ran with most of these pieces, and you’d have the makings of a life insurance commercial.

Okrent’s column drew a great deal of mail, some of which he published in a subsequent column. One letter, which made a strong impression on me and which I have remembered often since, made the following concise argument:

In making the case that The Times’s coverage of the gay marriage issue has shown a liberal imbalance by printing articles portraying gay marital bliss over articles describing potential marital strife, you confuse balance with illogical overextension.

During the civil rights movement, it was not incumbent upon newspapers to run articles about the risks of African-Americans drowning in public swimming pools as arguments against desegregating those pools.

LAURA NEWMAN

Astoria, Queens, July 26, 2004

Kristof and Okrent seem to want to cloud what should be a straightforward question of discrimination and equality in the interest of appeasing a (large) segment of the population that does not want to consider the question in those terms.

Same-sex marriage and adoption are civil rights issues. So many newspapers have had to face their institutional regrets for not covering the Civil Rights Movements of the 1940s, 50s and 60s in terms of objective right and wrong. That ugly period in media history should serve as a cautionary tale to media organizations working to cover modern civil rights issues. Perhaps the coverage of gay rights in the 2008 election indicates that in one area, at least, the lesson is finally being heeded.

This incredibly offensive and inaccurate headline appeared on CNN.com on Monday: “Ellen DeGeneres ‘marries’ Portia Rossi.” There was, of course, nothing pretend about the marriage–DeGeneres and de Rossi wed in California over the weekend. I personally don’t think that a marriage’s legal status is what should confer legitimacy on the union–I wouldn’t use scare quotes to call into question the legitimacy of a marriage between consenting adults in any state. But I really can’t imagine how anyone at CNN could perceive those quotes as ethical or accurate when the marriage in question was entirely legal.

The editors at CNN.com apparently came to the same conclusion because they changed their headline later in the morning to “Ellen DeGeneres reportedly weds Portia Rossi.” Hopefully, the original headline was the work of an individual that slipped through the editorial cracks, instead of the more troubling possibility that it was approved for publication by several sets of eyes. Either way, it should never have appeared. It should have sent up an armada of red flags to anyone who saw it. And the fact that it didn’t immediately do so suggests a culture–if not of overt homophobia, then of a tendency to advance socially conservative and discriminatory narratives about family life.

CNN.com rethinks its headline.