You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Journalism and Gender’ tag.

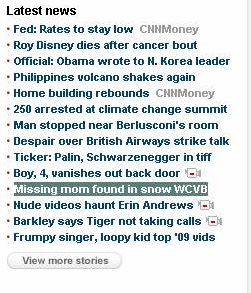

There are, of course, lots of big problems with journalism’s treatment of missing women. But I was struck yesterday by two headlines, both of which described their subjects as “missing moms.” Neither of the stories attached to the headlines—an AP story on NYT.com and a local news station’s story linked from CNN.com—suggested that the woman’s status as a parent was relevant to her disappearances (dropping children off at day care, or failing to do so, did figure into the stories of Susan Powell of Utah and Cortney Hudson in Massachusetts, but not centrally as far as I could tell).

So why would news organizations characterize the two women that way? I wondered initially if the women were full-time parents and the descriptor was being used as the equivalent to a noun describing a profession, as in a headline reading “Police Treat Missing Utah Banker as Criminal Case.” But both women have jobs outside the home. The only explanation I can think of is that the headline writers (and reporters themselves, who both used “mother” as the subject of their lede sentence) thought that defining these women by their relationships with their children would make the story more affecting for their audience. That or that the news organizations were making the (impossible and totally inappropriate) judgment that the women’s parental roles were somehow more central to their identity than other elements of their lives.

Of course the prospect of children losing a parent is affecting, and might easily have a place in a story about a missing person who is raising children. But choosing to elevate that element of a person’s life by literally defining her by it encompasses a judgment that no journalist is qualified to make. And if the search for affect was indeed the reasoning behind the “missing mom” meme, then the writers have violated what should be a standard of ethical journalism: it should rarely, if ever, prioritize a person’s value to others over her unique value as a human. We have a serious cultural problem if a story about a missing woman requires her to be a mother in order to tug at our heart strings sufficiently.

CNN.com front page “Latest News” 12/15/09, around 3:30.

It would be interesting to do a headline search in Lexis-Nexis for “Mom” and “Dad” and compare how often the described person’s status as a parent was of primary importance to the story. Without doing that, I can only say that it seems much less likely that a missing man would be described as a “missing dad” if his fatherhood were irrelevant to his disappearance. (Though he would almost certainly receive less coverage overall than his female counterpart.) He would be a “missing man” or possibly a “missing [representative of his profession].” Like “missing mom,” the latter choice reduces the missing person to one element of his life. While that reduction might also be problematic, most professions are less fraught with historical and sociological baggage than motherhood.

I realize that there are lots of important media ethics issues to discuss surrounding this week’s special New York Times Magazine issue about “Saving the World’s Women” (that white knight–inflected title would be a good place to start), but my friend Shannon pointed out a pretty glaring, if ultimately less weighty, issue: does the special text surrounding the online magazine preview really have to be pink?

I guess the online producers wanted to distinguish the “special issue” in some way, but I can’t interpret the decision to use pink in any way that doesn’t undermine the theme of many of the issue’s articles: that women’s struggles deserve to be taken seriously by policy makers and should be treated as “hard news” in the media. The pink color marks the weighty issues addressed in the articles (including women’s role in economic development, sexual slavery and human trafficking, and Liberian politics, among others) as belonging to a special interest, and places them in opposition to the magazine’s “normal,” “universal” fare.

Using pink to brand things for women is a historically suspect enterprise. For decades, manufacturers of all sorts have used it to pitch their wares to women while entrenching rigid gender roles and distinctions. The “pink for women” marker would have to be used in a pretty innovative way* for it to seem like a useful journalistic tool, and I don’t think the Times met that bar. I’m curious to see what the print version will look like.

*I would love to hear thoughts from anyone familiar with the breast cancer awareness campaign, which has clearly used “pink for women” to great and serious effect.